|

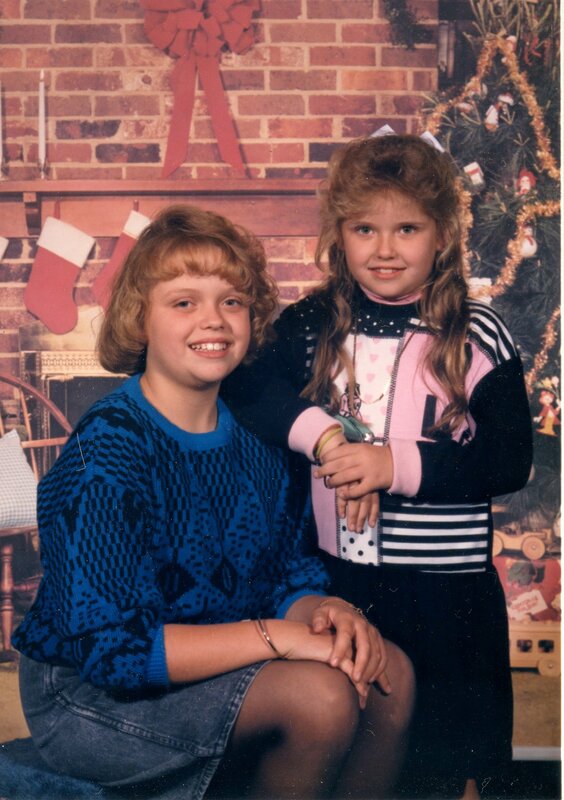

My baby sister stood in a glass box the size of a long gone, street side phone booth. She was seven years old. We were visiting the mall in the city where my grandparents had relocated - Spartanburg, South Carolina. She had been chosen from a crowd of people that had gathered around the booth in curiosity. I don't know if they thought they were being clever choosing a young kid for the show. If they did, they had never encountered a kid like my sister. She wore a mix of fear and excitement on her face. They closed and sealed the door to the box. As soon as it was secured, they turned on a blower that shot a high force of air up from the bottom of the box. Her hair blew. Then, they released the cash. A combination of bills, mostly ones, blew all around her. The timer began. She had thirty seconds to grab all she could hold and stuff into her clothes. If she was lucky, she'd snag the hundred dollar bill. She reached and grabbed faster than I had ever seen her little, chunky kid body move. Most of the bills flew out of her reach, but she didn't focus on what she couldn't get. She kept all the effort close. She clutched and snatched the money like all our lives depended on it. I can't remember how much she had when she left the box. I just remember how impressed everyone was with the amount. They said, "She might as well have grabbed that Benjamin!"

Everything that required and effort or attempt from me received 100%. 100% of frantic, desperate, overly zealous, hurried, raging fire me until I burned out. I felt the need to seize every opportunity that I felt confident I could use to achieve. It didn't matter what I was achieving, as long as people would think it was good. I'd give it my best regardless of whether or not it spoke to my heart or fed my soul. I'd do it simply because I could.

Dylan isn't the only teacher offering classes on the app, and soon I was saw another instructor, Melini Jesuadson, who offered specific handstand conditioning and training. She was trained in the Cirque du Soleil tradition, and made it look so doable. I picked up that program a month ago. I train strength and mobility with Dylan and a few others. Proprioception, approach and form is covered in Melini's program. I continue with my regular asana, pranayama, and meditation practice. In the class of the series Melini calls Handstands with Wall, she talks a lot about fear. What creates it and how to work passed fear. She suggests that a handstand practice can tell you a lot about your personality and your approach to life, especially challenges. Seeing handstanding as unattainable for so long gave me the impression that there wasn't much more that I could learn about myself and my body from its practice that I couldn't learn from doing foundational asanas like Warrior II. From the first time I worked through that class, I decided to use the practice as a tool to help me pin down patterns of behavior, my inner voice, and ways in which I react to challenges that I cannot readily meet. The practice of handstand would be the alchemical process for understanding these aspects of myself and transforming them into something more useful. It's been amazing. That brings me back to the story about my sister. My quest and self imposed obligation to take on every opportunity to earn money or credentials, like my sister's money grabbing adventure, is indicative of a scarcity experience creating a scarcity mindset. Growing up knowing that there was no and never was going to be a nest egg drew out the drive to grapple for those opportunities. It's common among people where I come from. It's basic sense of survival. Leah and I were taught that our mind was our best asset for providing a good life for ourselves. It was a combination of education and achievement that would secure a comfortable life. Our mother hoped too, that we could make ourselves attractive enough to possibly marry up. In 2012, according to a health issues poll conducted by the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky, eastern Kentuckians believed that their children would be worse off financially as adults than they are by a rate of 61%. I know that fear was real for my family growing up in the 80s and 90s. We were always encouraged to do well in school, go to college, and leave the mountains. Based on some comments female adult family members made to me and teasing in school, I decided early on that my looks could get me nowhere. I had to rely on brains. I had to use every available space to prove myself worthy of being chosen. Being from eastern Kentucky, I better never turn down a good opportunity to earn my keep whether or not it would be through a means I was passionate about and felt drawn towards. Another good, or better opportunity may never come. The grass is never greener. Accept the blessings you're given and be content. I've never been content in traditional roles, in the rat race, or selling my soul to the machine.

the outside world who could make it happen for her? After many rejection letters for my short stories, I had to give my time more to making a real living and raising kids. To land yourself in handstand there are variables that must have your attention. If any one component is off or unrecognized, you find yourself using a lot of energy without ever holding your body upside down. At worst, you'll fall feet over head on your ass. Every time I had randomly attempted handstand, I did so wishing that my brute strength would see me through and something would click. Like training wheels on a bike, I was too ornery to use a wall. I've fallen many times flat on my back, even the side of my face. It was as if in every approach I was setting out to prove myself right. Handstands were not possible for me, therefore I could justify it as not being part of my practice no matter how far I advanced my physical abilities. It was like my dream of being a writer. I was unlikely to score through serendipity. My effort needed to be toward achievable goals. It turns out that handstanding can be learned through a variety of clear methods. Step by step. Body awareness. Fun daily practice. I'm learning to be an upside down tree. Rooting into the ability to trust and believe in the unseen. Proprioception. Tangibly dreaming that in my middle age, I too will float and fly. Everything I've done, I've relied on my intellect and a force of effort to see me achieve. Because of that, I have kept goals smaller than the dreams of my heart, focusing on the obstacles and practicalities of life instead of potential for finding my purpose. We're now living in an era where it could be easier than ever before to find yourself making a livable wage as a writer and speaker on topics of personal growth and spiritual awakening. Many times I tried, taking the risk only when I was sure I could recoup from the pain of the fall. Taking the similar more pragmatic offers, always getting me close, but never the cigar. There is a way. A plan. A means to see my dreams alive under my hands and in the sound of my voice speaking to curious hearts. I stand feet together, hands shoulder width apart on my mat, and wrists in one line. I draw my navel in and up, lift my pelvic floor, and tuck in my lower ribs. I lock out my elbows and lift through my chest. From flat feet, I bend both knees, and spring with control off both feet. I push the ground away with my hand. I tuck up and find my big toes against the wall. I point my toes, press my ankles together, and squeeze my butt. I check core engagement. Arms straight. Eyes focused on the mat between my thumbs. All this I have practiced also laying down. One step at a time. Daily practice until I am practicing in the center of the room.

0 Comments

It's a marked and steady decline from my youth. It would take me an entire essay to explain to outsiders how living here is so unlike the urban American experience that it is as if you're from an entirely different country. Cultural norms, stereotypes, and etiquette are difficult to translate. It's a place that the developed world over still finds it politically correct to publicly and openly insult without most people thinking less of you for doing so. I've experienced it often firsthand, even from people I thought respected me. It may be worse from within our own state where whole swaths say, "We're not THAT Kentucky," when referring to the eastern part of the state. This place, more so the landscape, is my home. It is the substance of my blood. It's a place you should experience with a guide. Not just any guide. Not a romanticized reframing narrative of how its quaint, enduring beauty has been falsely portrayed. Not the resiliency narrative of a people perpetually oppressed and misunderstood as if they were the butt crack of society. The scapegoats. While both hold merit and are important pieces of the story, they are glorifying oversimplifications. It's far more complicated and nuanced. In not taking the time to convey or discern the big picture, many efforts of revival here shoot off their own toes, spin wheels, and self sabotage.

As much as this place is a part of me and what I want to keep in my life, there is a significant aspect of me that feels stifled, put down, and silenced. Working on my own groundedness, I have realized that the place I call home has never fit outside of a few mossy rocks and rolling mountain streams. That part of me wants to go. I imagine some sort of balance where my permanent dwelling is here or another part of Appalachia and I travel for my work. I have both worlds in that scenario. I have my landscape. The microcosm that created my body and foundations, while at the same time finding a wider interpersonal community where I can contribute through sharing embodiment workshops, yoga, and my writing. I can share with people who are interested in my perspective and experience, while I learn from them and their offerings. I have some beautiful opportunities to share some aspects of who I am here. Those chances keep me from feeling devastated. Yet, overall, I often feel a waste. I feel as if I am an odd peg with a chipped corner and one side swollen from getting wet. I belong to the set, but I don't fit well in the hole. The only time I don't feel awkward here is when I am teaching a yoga class. As soon as I end with "Sat Nam," the awkwardness floods back in. I have stopped being in public here aside from errands, school events for my children, teaching yoga, and wherever I can escape into the woods. There are ghosts here to dodge. Eyes that have shared with you behind a screen like a confessional, but won't look at you in the grocery store. Ducking behind displays on aisle end-caps to avoid small talk that is only cordial. Empty store fronts of inaccessible, unsustainable opportunity. A community you love so much it breaks your heart, but has only so many tiny spaces where you can squeeze in for a moment if you can behave not pushing too many wrong buttons. I've pushed those buttons, and like a mouse in a scientific experiment, received the electric jolt to associate with the behavior. I use the word "afraid" a lot. I'm adverse to small town drama because it is no longer worth the consequences. I'm happy to risk when my heart is passionately led. Other than my personal work in my little room and teaching yoga privately and at my local library, I haven't felt passion in a very long time. I have not felt the space for it. I have not had what I need to add fuel to what burns in me. The burning turns to sadness unexpressed and dies there uncomfortable to breathe.

I don't know my answer. I want to trust that the opportunity comes where I find that balanced place I mentioned before to feed my soul. I know that it is becoming harder for me to accept as when I visit away from here, even conversation in the checkout lines feels so much warmer and genuine. There are more spaces for me than I have the ability to fill. Here, I find myself more insular and reclusive than is healthy for me, and I don't have much impetus to change that in the current configuration of home.

Maybe... just maybe... I haven't been home yet. Earlier this year, the factions within the world of childbirth advocacy were up in arms once again spurred by the release of a study through the Midwives Alliance of North America Statistics Project which concluded that planned midwife-led homebirths for low-risk women lessened the use of intervention and increased the incidence of physiological birth while not increasing adverse outcomes. Immediately, there were rebuttals from the anti-homebirth movement calling the data flawed and citing research conducted from within their own camp where they concluded that babies born at home with midwives were four times more likely to die than babies born in hospitals. Both groups question the other’s methods. Both groups say that their way is potentially “safer”.

These arguments of risk are not limited to homebirth vs. hospital birth. Take VBAC (vaginal birth after cesarean) for instance. If you Google “is vbac safe”, all of the top choices will tell you that for most women it is. Some of the sources even say it is safe for up to 90% of women who would seek VBAC birth. Despite this body of evidence that shows VBAC is a reasonable option for many mothers with a prior cesarean surgery, only around 8% of women in the United States VBAC. Women seeking VBAC are given numbers and claims about its safety that don’t add up in order to be dissuaded. Yet, even with clear evidence in support of VBAC being a safe option, those who consider themselves advocates of VBAC are also giving women unrelated risk scenarios in order to make a comparison, potentially clouding a person’s perception of the risk. As you can read in Jen Kamel’s (www.vbacfacts.com) blog post “Lightening Strikes, Shark Bites, & Uterine Rupture,” comparing two dissimilar events can be problematic when trying to convey risk to someone. Whose responsibility is it to convey the risks of pregnancy and birth to women? Is it possible to explain your understanding of the risks of a choice in unbiased terms or by simply adding your understanding of the risks in question are you imposing your choice onto another? Assessing or sharing the risks and benefits of choice is not an easy spot to be in as a mother, a birth professional, or a care provider. It is inevitable that we will feel that we or someone we know could have made a better choice. There may even be times when we feel so strongly about the choice of another that we feel we must save them from it without asking ourselves whose choice it is to make and whose responsibility are the consequences of choice in the childbearing year? Do numerous studies and the varying opinions of “professionals” help make clearer the inherent risks of our choices in maternity care? Regardless of fact, the discernment of risk is largely individual and is impacted by the personal values, beliefs, and experiences of a person. There is no one way in which a person understands and assesses risk, and some of the ways in which we process risk can compete with one another. It is apparent that when discussing risk, it is near to impossible not to impress personal assessments onto your explanation. What is right for one mother may not be right for another. Accepting or avoiding risks of options in childbirth is not the responsibility of anyone but the person faced with the choice. Let us take VBAC as an example. One mother may have experienced her prior cesarean surgery as traumatic. Maybe she suffered PTSD as a result of the experience. She felt belittled by her care provider and felt like the surgery she experienced was unnecessary. Faced with the choice of VBAC or repeat cesarean, this mother could feel that choosing a setting where she is fully supported in a TOLAC (trial of labor after cesarean) will give her the best chances at VBAC therefore allowing her to remain in control of her birth and give herself and her baby the safest possible start. This mother may also after researching her local options decide that the location best suited for her birth would be home. In making these choices on her own terms and being supported in preparing herself for this birth, this mother is eliminating fear. The risk 0.5-1% risk of uterine rupture seems so very small compared to the potential loss of control, feelings of disrespect, and feelings of harm she had experience while undergoing cesarean before. Another mother experienced a cord prolapse after her waters released during her first birth. She had been laboring naturally and moving as she wanted throughout her labor until that point. Fortunately, she was at the hospital with competent care providers who assessed the situation quickly and her baby was delivered via cesarean with no lasting complications. When asked if she would like to VBAC for her next delivery, she asks for a repeat cesarean. The thought of potential uterine rupture or another cord prolapsed overwhelms her and she feels safer if she can plan her birth. She wants to be in control of the situation and allowing the doctor to perform another cesarean, while she is awake and everyone is healthy does so much to reduce the fears she has of complications. The increase risk of problems in future pregnancies seems low to her compared with the potential for complications in birth that she has already experienced. The “right” choice for a person is subject to time, place, and experience. The “right” choice is not unchangeable. It is as fluid as the human condition. It is an individual choice. Our current climate of debate about the safety of our various options in childbirth and the active pursuit to limit or eliminate options from women is to put the whole of humanity in danger. It is to decry the personal and to take away the right of an individual to accept the responsibility for the choices they make for themselves and the choices we make as a parent. Neither of the women described above are making a “selfish” choice as critics on both sides have accused women. They made the choice that gave them the space to transition into the mothering of this new person in safety and peace. It does us no good to spend countless hours debating these studies never one to satisfy the other. It does nothing to improve the standards of maternity care in this country or the world. All it does is breed confusion and misinformation, and results in skewed judgment and blame. We can cry out for the right to choose. We can cry out for protection. We can cry out for mothers to take responsibility for their births. The crying will be for naught if we cannot accept that assessment of risk is individual and in order for pregnancy, birth, and yes, even parenting to be healthy there must be room left for personal decision making. If you are called to be with women in birth, you must regard them as individual and their experience as their own. Facts will be facts. Birth will be birth. While I appreciate and very much respect the studies and research being done in the name of evidence based care in childbirth, the torch we should be carrying during this time is the sanctity of the mother in birth, the rightness of personal experience, and the space for empowered decision making, for how can we accept responsibility for a decision we feel we did not make. |

AuthorKelli Hansel Haywood is the mother of three daughters living in the mountains of southeastern Kentucky. She is a writer, weightlifter, yoga and movement instructor, chakra reader, and Reiki practitioner. Categories

All

Archives

September 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed